Runoff elections that went wrong

What could possibly go wrong in the next week of French presidential elections?

The epic contest for the French presidency is being conducted according to the rules of two-round runoff voting.

The world is watching with fascination as four key contestants – centrist independent Emmanuel Macron, the nationalist right’s Marine Le Pen, the centre-right-conservative Francois Fillon, and the radical left’s Jean-Luc Mélenchon – are locked in a tight battle for the Presidency of France.

The best-placed two from Sunday’s first round of voting go head-to-head in the second round of voting on May 7.

The candidate of the long-established French governing party, the Socialists, has fallen to fifth place, with apparently no prospect of success. Six further ‘micro’ candidates are also in there, absorbing small percentages of votes from the political left and right.

The system is now positioned to elect a possible president anywhere from the political far left to the far right.

As the first round is held and counted, the electorate briefly loses control over the outcome, because no-one can be entirely sure which combination of two candidates will go forward to the second round.

The two-round runoff method serves well in systems where candidates of established left and right parties reliably take the first two places. Voters supporting alternative candidacies can make their protest votes known without hesitation, then re-assess the final choice and come together behind a nationally accepted winner in round two.

All but one of the modern French presidential elections have followed that path.

But two-round runoff voting can also malfunction, at least in terms of electing a winner into a climate where a majority would have really preferred someone else. This post examines three ways the method can go wrong.

The single-side-of-politics scenario

The first scenario is best exampled by the one French presidential election that did not follow the model – the election of 2002.

What went awry in that case was that there were four significant contenders, among which the political left divided their vote behind many candidates, one centrist performed well, and the political right split between two candidates.

The numbers of votes in the first round fell out just such that the highest-placed two candidates were the two from the right:

- Jacques Chirac (UMP – the orthodox right) – 19.9%

- Jean-Marie Le Pen (Front National – the far right) – 16.8%

- Lionel Jospin (Socialists – the centre left) – 16.2%

- François Bayrou (representing a centrist party) – 6.8%

- At least six minor left-wing candidates with votes between 3% and 6%

- A final six various micro-candidates with very small support

The key event explaining what happened was that several left-wing minor candidates ran, hoping to raise their political profiles and secure policy trade-offs through a noticeable first-round result, but all of them assuming that the Socialists candidate Jospin would win in the second round, forming a presidency they could benefit from.

But it turned out otherwise. Chirac, the incumbent president, suffering strong negative approval ratings in the country, got to face off against Jean-Marie Le Pen (father of Marine Le Pen, the leading candidate in the 2017 race), an extreme candidate with massive disapproval ratings.

Chirac won the final round vote in a massive landslide: 82% – 18%.

No commentator has ever claimed that Chirac was actually wanted by over 80% of the electorate, of course. The country simply united behind the urgent task of rejecting Le Pen.

Research into voter opinion was later to conclude that certainly Jospin, and possibly also the centrist Bayrou, would have been preferred to Chirac (and no doubt Le Pen) by a majority of the French electorate.

In fact the evidence is pretty conclusive that Jospin would have beaten any other candidate in all one-on-one contests that might have been held.

So in 2002 the two-round system gave the French a president they didn’t want, while someone they really wanted more was nominated and had been fully weighed by the electorate during the campaign.

Obviously the rule that eliminates at once all candidates who placed third or worse in terms of ‘first preferences’ was the immediate cause of the problem. The problem is that the candidate most preferred over all others can sometimes be placed third (or possibly, but highly unlikely, fourth or lower) on those first preferences.

But the voting system as established in France does not allow for the effective management of such a scenario, and instead gives the electorate an unwanted election winner.

The jungle primary scenario

Another form of ‘malfunction’ manifests in four American states, under what is termed the ‘open’, ‘jungle’ or ‘blanket’ primary system.

America has an intensely strong two-party system, so the way they use these voting rules is not quite the same as the standard two-round runoff voting system.

Instead what the Americans do in these states is try to allow some additional voter choice by turning the primary round of elections – which in most other states is used to allow supporters of each party to settle behind one nominated party candidate for the later final election – to sort out the fate of multiple candidates of both parties at once.

In jungle primaries, several candidates from each of the Republican and Democratic parties all face a first round of voting as a single contest. Only the best-placed two candidates then go forward to the final election round.

In recent elections in Washington state and California, on a few occasions the system has unfortunately thrown up two candidates of the same political party – two Democrats, or two Republicans (or one party candidate and an independent). A large section of the electorate thus loses out on having any nominee for the final contest.

Importantly, voter turnout is usually much lower in the primary round than in the real election, potentially distorting the political result. (Louisiana, another state using this system, at least avoids that problem by conducting the first round on the national election day, and the final round a few weeks later).

This system can also be distorted by the number of candidates each party puts forward. If one party runs just two candidates, and the other nominates say five or more, the party with just two has a boosted chance of taking the top two spots, and going into the final election. This can even happen if the former party is generally the minority party in the electoral district.

But even where such party-limited final rounds don’t happen, the jungle primary system can still result in the final winner being someone that a majority of the electorate didn’t want, with another preferred winner being among the original nominees, but swept aside by the two-round system.

That can happen where the two best-placed primary round candidates, each from a different party, have a core of supporters sufficient to get them a top spot, but also have major public approval negatives.

If more acceptable compromise candidates, which would have attracted supporters in the final round, are hidden back in third or fourth place on the round one results, the result can – like the French 2002 presidential race – be that a winner takes office even though someone else would have been preferred in their place.

Perhaps the most entertaining (although sadly undemocratic) example is the 1991 election contest for Governor of Louisiana, cheerfully told as the opening story of William Poundstone’s 2008 book Gaming the Vote.

In a complex multi-candidate contest, during which the incumbent Democratic governor brazenly switched parties to run as a Republican, dividing that party’s voters, the best placed two candidates after round one were the Democratic former governor Edwin Edwards – constantly dogged by allegations of corruption and disapproved by well over half the electorate – and the surprise leading Republican candidate David Duke, who rallied just enough support to place second despite his immensely controversial views and Ku Klux Klan background.

Louisiana voters in 1991 thus ultimately had to choose between ‘the lizard or the wizard’. Finding Duke the more unacceptable of the two, they chose the lizard, Edwards.

(After his fourth and final term as governor, in 2001 Edwards was finally found guilty of racketeering charges and served eight years in prison. Post-jail, Edwards didn’t give up politics, though. In 2014, at age 77, he ran for a seat in Congress, remarkably placed first in his jungle primary, but was soundly defeated in the final runoff round.)

The scenario of extremes

Finally, there is the awkward scenario where the two finalists represent the extremes of politics.

Perhaps the best example is the eventually tragic election for the first post-revolution President of Egypt in 2012.

By way of background, a popular revolution in 2011 had swept the old Mubarak regime from power, and in turbulent political conditions the country staggered towards its first democratic elections in decades. The conditions for free campaigning were reasonable – if imperfect – but the state of development of political parties was hardly stable, after being seriously suppressed during the old regime. Almost all political forces were raw and new, and public opinion was fluid and hard to analyse and predict.

Here there were five significant candidates. Their backgrounds, and their votes in the first round, were as follows:

- Mohammed Morsi, the leading candidate supported by the Muslim Brotherhood, a movement with a solid minority supporter base, but regarded with deep suspicion by a majority of the electorate (as well as the political establishment, the powerful military, and the United States) – 25%

- Abdel Moneim Aboul Fotouh, a more moderate and open-minded Islamic-platform candidate – 17%

- Hamdeen Sabahi, of the Nassarist Dignity Party, an opponent of the old regime and prominent participant in the recent revolution – 21%

- Amr Moussa, a former foreign minister and secretary-general of the Arab League, internationally respected and regarded as politically moderate and professional– 11%

- Ahmed Shafik, the candidate promoted by the old political establishment and the military, with a core of support from that base but – for the same reason – strongly rejected by the democratic movement and wider public opinion – 23%

This was not a perfect election. The first round voting saw a disappointing 43% turnout. There were allegations that the regime had issued up to 900,000 voter ID cards improperly to military personnel to assist Shafik, who ended up being only around 700,000 votes ahead of Sahabi in the race for second place.

Analysis and polls indicated that Morsi and Shafik were the two candidates most rejected – indeed strongly rejected – by a majority of voters. Yet by winning the two highest minority votes, they became the two candidates that went into the runoff round.

Mohammed Morsi was elected President of Egypt, but a clear lack of majority support in the community left his government with limited legitimacy, paving the way for a military coup (image: Wikipedia)

In the second round of voting the electorate distrusted the old political establishment more, and chose Morsi.

Morsi’s government then set about trying to introduce Muslim Brotherhood policies and bring Brotherhood individuals into power.

In short order the public, and the military, rejected what was happening, ultimately leading to a military coup, the political arrest and trial of Morsi, further civil disorder and more deaths.

In the years since, Egypt has seen a military government and the establishment of a ‘managed democracy’, with the coup leader now serving as the elected president. The nation is at least calm – which an anxious people needed with serious civil disorder breaking out in several of their neighboring nations.

The opinion polling needed to fully analyse the alternative possibilities of the 2012 vote is not entirely conclusive, yet there is near-certainty that Sabahi would have beaten either of Morsi and Shafik in any runoff election. There is a reasonable likelihood that either of Fotouh or Moussa might also have done so.

If those alternative prospects are correct, then in technical terms Morsi and Shafik were actually the two lowest ‘Condorcet losers’ out of the five candidates – that is, the two candidates who would each lose to any other single rival candidate.

The only way Morsi could have won the election was the one pathway that actuallty did happen: having the candidate of the despised establishment, Shafik, as his final rival.

Out of the three more acceptable compromise candidates, the most favoured was probably Sabahi. But we will never know, thanks to the voting system they used – and also to the turbulent condition of Egyptian politics at the time.

Hamdeen Sahabi might have been President of Egypt, but for the two-round runoff voting system (image: Aatkco)

What all these scenarios have in common is that an election winner takes office while there remains on the sidelines another candidate who did not win despite nominating, running an election campaign, and being preferred by the electorate to the actual winner.

Sometimes the way these election results are collated can conceal the support for the alternative, or leave the matter being disputed by observers. In other cases it can actually be obvious, or at least attested by clear opinion polls, that the electorate wanted a specific unsuccessful alternative winner.

The result is not merely a failure of democratic process, but leaves a winner bogged down by an ongoing state of illegitimacy, hindering their ability to govern with public support, and damaging the public’s often fragile faith in democratic institutions.

The French presidential race of 2017

One of the problems mentioned above may be about to manifest in France. The political right could take the two top spots, in the form of Le Pen and Fillon, just as happened in 2002. Alternatively, the two most extreme of the four leading candidates – Mélenchon and Le Pen – could be the finalists, somewhat as happened in Egypt in 2012.

In either case the nation’s most preferred candidate might not be chosen, because their first round place in a large field happens to be third or lower.

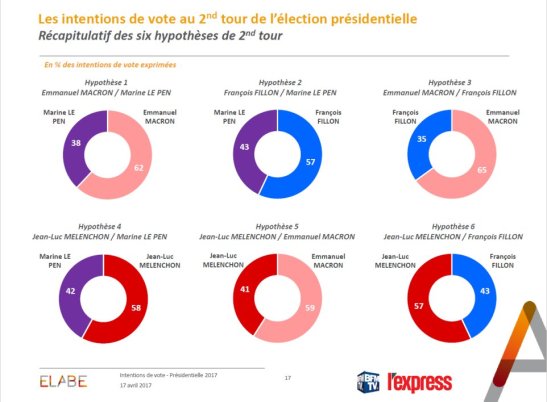

Recent French opinion polling has attempted to model all the possible two-candidate scenarios between the four current presidential candidates.

(image: BFM TV – late April)

Emmanuel Macron wins all three of his contests on this polling. Mélenchon wins two, Fillon one, and Le Pen none. But it all depends on which comparison actually matters on May 7.