Next UK electoral boundaries will leave ‘youth surge’ out

By late 2018 Britain is set to have new constituency boundaries for future House of Commons elections.

But they will be based on December 2015 voter registration numbers, leaving out of consideration the surge of young voters added to the electoral rolls in the past year.

Under current arrangements, 2.2 million voters who joined the rolls this year will not be counted in the process for drawing electoral boundaries until nearly the year 2030.

Britain’s system for refreshing the boundaries of the single-member constituencies for the Commons was revised in 2011. A series of delays since then have meant that the boundary changes, originally meant to be ready for the 2015 election, are now due to be finalized in mid-2018.

Assuming the current British government survives at least 18 months, the next general election will use the recently proposed new boundaries.

The modernized system is based on independent commissioners and objective criteria, so there is no US-style gerrymandering.

As part of a package of measures advanced by the 2010 Conservative-Liberal Coalition government, the size of the House is to be reduced from 650 members to 600.

The 2011 reforms also specified that the number of seats allocated to each of the four British ‘countries’ – England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland – will be reallocated in proportion to the numbers of registered voters in each region.

England will now be allocated 501 seats in place of the current 533. Each of England’s nine internal ‘regions’ will in turn be allocated a specific number of seats.

Scotland’s allocation will fall from 59 to 53 seats. Northern Ireland will lose one seat, from 18 to 17.

The biggest impact will be in Wales, which will fall from 40 seats to 29.

Under what is known as the “Sixth Periodic Review” of constituency boundaries, four independent country Boundary Commissions (one each for England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland) begun drawing the necessary new constituency boundaries in 2016. Extensive rounds of public consultation built into the process meant that the timetable takes almost two years to complete.

The early UK election held this month meant that the recent election was conducted on the same constituency boundaries used in 2010 and 2015. The English, Welsh and Northern Irish boundaries were last reviewed between 2006 and 2008. In fact the current boundaries for Scotland were first used for elections in 2005.

The political impact of the proposed new boundaries will be the focus of everyone’s attention. British psephologist Martin Baxter has already estimated that had the new boundaries been in effect the 2017 election results would have seen a more or less identical political outcome, with the Conservatives 3 seats short of a majority and looking for support from the Irish Democratic Unionist Party.

The modern boundary-making process is logical and objective, but there will very likely be a major controversy in the coming year over what registration data should be used.

The current law specifies that the registration data for the boundary reviews must be that which was recorded in December 2015.

Reform of the British electoral law in the past decade has progressively introduced a modern system of voter registration. The system now requires individuals to be responsible for updating their own registration details.

Commencing in 2015, this has meant that the UK’s electoral register, now of nearly of 47 million voters, has undergone a thorough refresh in recent years.

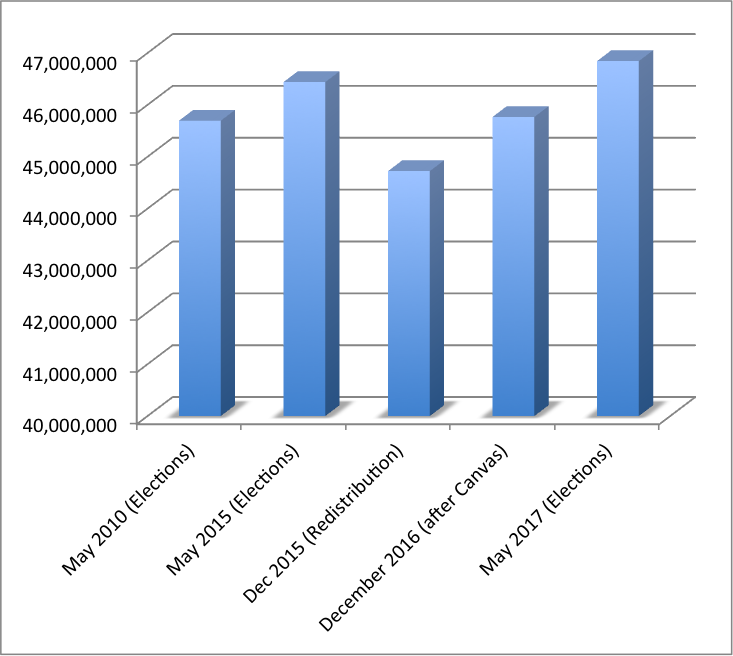

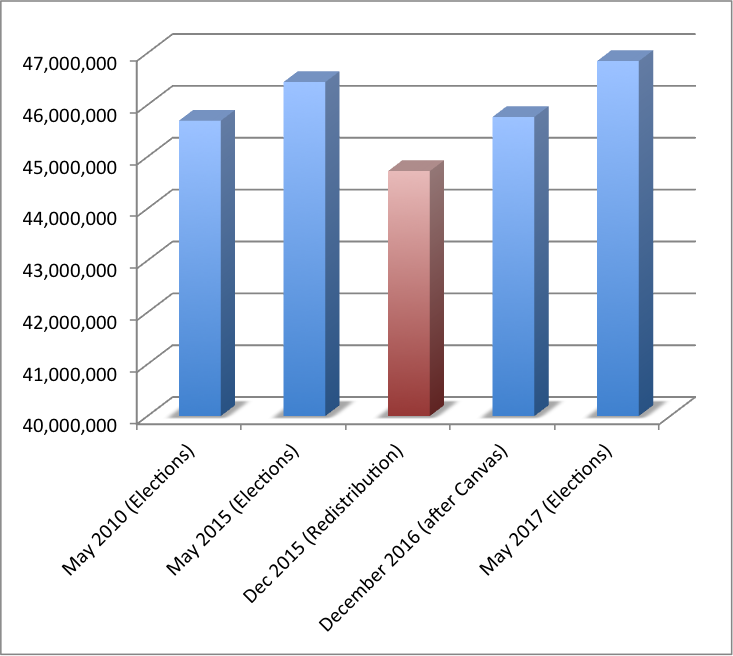

When Britain voted seven years ago, in May 2010, there were 45.7 million names on the registers. (Even after the recent reforms, the system is still based on separate registers kept by each local government authority, rather than one national register.)

By the elections of May 2015, the register total had grown to 46.4 million names.

After that the impact of the new registration system began to kick in. The immediate result was actually a sharp fall in the number of names, dropping 1.7 million names to 44.7 million by December 2015.

Why did the registration numbers fall? Given that there was no matching demographic fall in Britain’s population, the explanation is almost certainly that there had been duplicate names on multiple registers, old records for deceased persons, and so on.

(If the registers were over-stated, that means that turnout estimates for elections up to 2015 are suspect, and may not be comparable to the most recent results. But that’s another issue.)

Then from early 2016 a number of events happened to start boosting the rolls up again.

Firstly, there were election events, which always result in bursts of registrations and updates of voter details.

Regional elections were held in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and also for the Greater London Authority, in May 2016

Local government elections were held in different parts of the country in each of May 2016 and May 2017.

Then there was the dramatic Brexit referendum in June 2016.

All these events would have caused additions and updates in the register databases.

But in addition, in accordance with the modernized register system, the nation’s local authorities spent the second half of 2016 engaged in ‘canvases’ of the population. These exercises involved electoral staff working in local communities, actually going door-to-door, encouraging new registrations and checking existing register details.

By December 2016, when the canvases were finished, the aggregate size of the registers – collated by the Office of National Statistics – had increased again to 45.6 million names.

Now likely cleared of duplicates and old data, these would have been the most accurate UK electoral registers ever.

And then along came the unexpected 2017 general election.

Britain’s electoral registers are now larger, and probably more accurate, then ever

In the space of a matter of weeks between April and May this year, the registers grew again by over a million additional voters, leaping from 45.7 to 46.8 million names. Widely thought to be a surge in young voters registering for the first time, the national register total reached its highest point in history.

The election results have been dramatic. But behind the scenes, with their official timetable unchanged, the boundary reviews are continuing. That timetable anticipated preparations leading up to a general election due in the year 2020.

So all the proposed new boundaries – which were published in draft form late in 2016 – are still based on the electoral register data from December 2015.

That data is now 2.2 million voters below the level reached a month ago, at the deadline of May 22 for register updates to be valid for voting at the June 8 elections.

So the new electoral boundaries, proposed for use for any election held from late 2018 and for around a decade after that, will not take into account the millions of British voters who registered in 2016 or 2017, including the ‘youth surge’.

The current UK constituency boundary review legislation requires the use of December 2015 data that is missing 2.2 million current registered voters

With the boundary law indicating that reviews should be conducted around every 8 years, the next review should not come around until the year 2026. Given the history of deferrals, it is not certain that even that date will be met.

This means that an 18-year old voter who enrolled in the lead-up to this year’s election might not be taken into account in drawing constituency boundaries in Britain until an election as late as the year 2030, by which time such a person would be around 31 years old.

Any exercise such as this requires a data cut-off date and adequate time for work and consultation. Review timetables must also try to avoid actual elections if they can.

But the current timetable, and the data it will use, has now fallen behind very significant events in British democracy.

Could the boundary commissions refresh the process, delaying it again to recognize that they were working towards a 2020 election, but are now nominally working to one due in 2022?

Of course that is possible, but it would require Parliament to alter the timetable details in the current legislation.

Would the current minority Conservative government be willing to propose such an amendment, given that it was the ‘youth surge’ that appears to have deprived it of its majority?

Counting the additional 2.2 million voters could materially alter the number of seats won by parties, especially if the next election is close, or remains in ‘hung parliament’ territory.

Yet failing to reset the timetable would treat the 2.2 million recent additions to the register as if they did not exist.

Whatever the merits of the arguments, Parliament is going to need to vote on the boundary changes in any case, because the current legislation requires Parliament to hold an up-or-down vote to accept the new boundaries proposed by the Commissions.

Under the current legislation, at some point before mid-2018 the current, politically hung Parliament will be asked to vote on the proposed new boundaries that have been drawn based on the 2015 data.

The Conservative party might well prefer a boundary outcome based on data leaving out the recent registrants. But most other parties in Parliament will likely disagree.

And ironically the government’s not-quite-a-coalition supporters, the Irish DUP, have themselves previously objected to the changes, which see Northern Ireland lose one seat.

Either way, because of the way the current law stands, the new British Parliament cannot avoid this issue – other than by failing to act at all, and allowing the increasingly dated constituency boundaries drawn back in 2006-08 to be used yet again.

Pingback: UK Conservatives’ early election call cost them majority | On Elections