Virginia state vote ends in farce

The first election to be resolved in 2018 is actually for an American state legislature voted for last November – but the election has ended in farce.

The Virginia House of Delegates will – for the moment – have a 51-49 majority of Republican members, after the final seat was awarded by drawing a name from a bowl.

Last November Democratic voters turned out in large numbers for an under-noticed mid-term election, winning the statewide vote for House seats 54% to 45%, capturing 15 additional seats and destroying the Republican’s previous 66-34 advantage.

But the highly gerrymandered boundaries of the 100 seats have delivered the Republicans a narrow majority anyway.

For a few days prior to Christmas it appeared the House seat numbers would be balanced 50-50, with a recount of votes in the 94th district awarding the seat to the Democrat candidate by just a single vote.

But in a dubious maneuver, immediately after the recount the Republican candidate’s lawyers pressed the electoral panel of judges to reconsider the nature of a single ballot paper that had been ruled invalid because both leading candidates’ names had been marked.

The panel controversially decided to accept the paper as a valid vote for the Republican candidate – David Yancey – thus causing the election to be tied at 11,608 votes each. The decision appears at face value to be in defiance of the statutory rules and precedents for considering such ambiguous ballot markings.

The bowl from which the 94th district seat winner’s name was drawn yesterday

Under state law, a winner for the seat was yesterday drawn at random, and Yancey’s name fortuitously came out of a bowl, creating the Republican’s one-seat majority.

Democrats are understandably outraged. Their successful candidate for Governor won his election on the same day by 54% to 45%, and the aggregate of votes cast for the House members was similar: 1.29 million votes cast (53%) for Democratic candidates to 1.08 million (44%) for Republicans.

But Republicans will now be able to oppose the Governor’s program with 1-seat majorities in both the House, and also in the State Senate elected in 2015.

For the interested reader, what follows below is a detailed account of how the voters of Virginia have been brought to this deeply unsatisfactory situation

*

The Virginia House of Delegates has a long democratic pedigree, being the successor of the state’s House of Burgesses, founded in 1619.

The Virginia House of Delegates, America’s oldest parliamentary assembly (image: Germenna Community College / Wikipedia)

The oldest elected assembly in the American continents, the House will next year celebrate its 400th anniversary.

But sadly, the results of recent elections mean that legislative politics in Virginia barely deserves the description ‘democratic’ at all.

The current situation is driven by extreme gerrymandering implemented by the Republican party in 2011, as well as low voter turnouts,

To understand how this situation has come about, we need to go through the events that have unfolded since the beginning of the decade.

Virginia is known as a politically ‘purple’ state – one were the electoral returns for Republicans and Democrats in recent decades has been reasonably competitive, moving in a range between 45% and 55%, and not seeing any extreme outcomes.

But during the current decade the Democrat vote has been noticeably predominant. For statewide elections since 2012 Democrats have generally polled between 50% and 54%, with Republicans polling 45% to 49%.

US legislative electoral boundaries (for both state and national elections) are re-determined every decade after data from each annual Census is released. The last ‘redistricting’ period was thus during 2011 and 2012, in readiness for elections held in November 2012.

Regrettably, in the United States electoral district boundaries are determined by the state legislatures – made up of the very people whose self-interest is directly at stake.

(A few US states have recently passed laws – or had voters enact constitutional initiatives – handing the issue to independent commissions specifically to get away from the self-interest problem.)

State Governors must also agree to the laws promulgating new electoral boundaries, adding an additional potential partisan element.

During 2011-12 the Republican party held the office of Governor of Virginia as well majorities in both houses of the state congress. In a clearly partisan process, the new boundaries were drawn to heavily concentrate Democratic-voting communities into the smallest number of seats they could, and thus leave Republican-voters in less extreme, but still decisive majorities in a majority of the districts.

This was not isolated work, but formed part of a national campaign coordinated by Republicans in response to their 2008 loss of the presidency to Barack Obama.

The national Republican party gerrymandering drive, known as the REDMAP Project, was aimed at helping recover control of the US congress. The whole disturbing tale of the effort across multiple states is chronicled in David Daley’s book Ratf**ked.

November 2012

In November 2012 the Virginia gerrymander was put to its first test. Being a presidential election year, Virginia voters turned out in respectable numbers, with between 68% and 71% voting for the various elected offices on their ballots.

Democrats won a small advantage, with President Obama winning the state for a second time with 51% of the vote to 49%.

The Democratic candidate for the state’s US Senate seat – former Governor Tim Kaine, later to be Hillary Clinton’s presidential running mate – also won election, by a clearer margin of 53% to 47%.

But across the state’s 11 national House of Representative districts, Republicans had the slight advantage, winning 50% of the total votes cast to 48% by Democratic candidates (2% of the vote went to candidates from other parties and independents).

All 11 of these congressional districts were contested by candidates from both parties. As we will see, this was to be the last time in the decade that any election in which every voter statewide could chose between candidates of the two parties would result in a Republican majority of votes.

At a result of 50%-48%, a reasonable expectation of sharing out the 11 seats might be 6 for the Republicans and 5 for the Democrats. But the gerrymandering proved its worth at its very first outing, with the Republicans in fact winning local majorities in 8 seats to the Democrats’ 3.

2012 election results like this across several states added to the creation of a Republican majority in the national Congress. Nationwide, Democrats had won 58.9 million votes to the Republicans 58.5 million*. Yet the control of the House of Representatives was inverted, with Republicans winning a handsome advantage of 234 of the seats to the Democrats’ 201.

(*Such national vote aggregates suffer from the problem that each party fails to nominate candidates in a small number of ultra-safe seats, meaning that the nationwide vote totals are not strictly comparable.)

The outcome in Virginia, where Republicans contrived a five-seat advantage instead of a one-seat one, made its small contribution to the resulting political control of the House of Representatives.

Gerrymandering is not the whole cause of the problem of these ‘inverted’ electoral results. Electoral analysis do generally believe that there is some effect of distortion due to innocent concentration of voting habits, with the major US cities having very high majorities of Democratic-voters, and Republicans having similar massive majorities of the vote in rural, mountain and deep South regions.

Meanwhile the more contestable suburban and regional areas show more spread-out political support that very mildly favours Republican wins.

But the collective effect of gerrymandering, which reached new levels of sophistication in 2011-12, was now transparently obvious. Estimates of the Republican advantage in the 2012, 2014 and 2016 national House of Representatives elections range generally from 15 to 22 seats.

November 2013

Virginia is one of just two US states (the other being New Jersey) that runs the 2-year cycle of elections for their state lower houses in odd-numbered years. So the Virginia state elections of November 2013 were the first outing for the newly gerrymandered boundaries of the 100 seats in the state House of Delegates.

Perhaps discouraged by the obvious implication of the boundaries, Democrats put in a lackluster effort at nominating in 2013, with only 67 contestants in the 100 districts. Essentially, they abandoned 33 seats to the Republican party without a contest.

Republicans were more motivated. Having divided over tax policies during the preceding term, and with the ‘Tea Party’ wave of grass-roots rebellions still active, there were fights over primary nominations for incumbents for the first time in several years. Republicans contested 76 seats, leaving 24 for Democrats unopposed.

But overall election turnout was well down on the previous year’s presidential election, with only 39% of registered voters attending the polls.

Here we need to add another perspective to election data, to render results comparable across multiple years. Turnouts in US elections vary so greatly that simply using party vote shares in each election can be significantly misleading.

A better comparison can be made by using the proportion of registered voters who turn out to support parties in each election.

(An even better comparison would use the proportions of all eligible voters, rather than merely those registered, since in many US states even registration has become a politicized affair, with active suppression of registering on a partisan basis. Virginia registrations stood at 5.43 million in 2012, then fell to 5.24 million in 2013, rose slightly to 5.28m in 2014, fell again to 5.19m in 2o15, then rose noticeably to 5.53m in 2016, before falling again to 5.49m in 2017. Clearly the numbers rise and fall with the importance of elections, but in contrast to nations with comprehensive, non-partisan registration systems such as Australia, these numbers are obviously not tracking solely to the demographic facts as ideally they should.)

One general observation in US elections is that election turnout by Democratic voters varies more than does Republican turnout. Democrat supporters turn out in larger numbers in presidential elections, and also (if less so) in elections involving state governors, but are poor attenders of polls in years with only legislative elections.

Republican turnouts also vary in different years, but in a less broad range.

That’s why as a general nationwide rule, Democrats do better in presidential election years, and Republican candidates in mid-term elections. (The year 2017 has proved to be an exception, with high relative motivation by Democratic voters in special elections to fill several vacancies and – as we will see – in the 2017 Virginia elections.)

But back to the 2013 elections. The Republicans had entered into more House of Delegates seat contests than their Democratic opponents, and collected more aggregate votes as a result. 20.8% of registered voters supported Republican candidates, to 15.6% for Democrats. On these relatively low turnout results, the Republicans achieved a massive legislative majority, 66 seats to 34.

It’s not al all likely that more Democratic candidates would have made much difference, since they would have been contesting mostly safe Republican seats. The Republican voters simply turned out in greater numbers and won this election.

In a decisive election result, gerrymandering matters less (or rather, it is perhaps less detectable).

But nonetheless, the combined effect of advantageous boundaries and the resulting discouragement of Democratic campaigns, together with the traditional lackluster Democratic turnout in mid-term elections, crafted for the Republicans a clearly larger House of majority than a true reflection of the community.

How can we be sure? Because another three elections were held that day – the statewide races for Governor, Lieutenant Governor, and Attorney-General, of which all three were won by the Democratic candidates.

Democratic candidate for Governor Terry McAuliffe won by 47.8% to 45.2% of the vote.

Where a total of around 1.09 million voters had cast votes for Republican House candidates, remarkably even fewer – 1.01m – voted for the Republican candidate for Governor. Instead of the 0.82m votes for Democratic House candidates (in just 66 seats), a much higher 1.07 million voted for McAuliffe.

Similar results were recorded for the other two executive positions. So overall, those voters who turned out in 2013 actually were slightly more Democrat-supporting, despite the low turnout. But for many of them the absence of a Democratic candidate on the ballot in their district meant that they recorded no House vote.

(Indeed, many of these ‘Democratic voters’ might actually have marked votes for the Republican House candidate, in the numerous seats where they were in fact the only candidate at all.)

Had the partisan numbers of votes cast for the three executive positions also been cast in a House election without gerrymandered boundaries (or better still, one with multi-member districts to also even out the innocent effect of demographic geographical distortions), the voters who turned out in 2013 might have elected a House of Delegates of around 52 Democrats to 48 Republicans.

Instead, the actual election result was 34 seats to 66 – not merely an inversion, but nearly a two-thirds majority for the party that had fewer statewide voters.

November 2014

November 2014 was a relatively quiet election for Virginians, with their other US Senator the only race of significance.

With a turnout of 40%, incumbent Democrat Senator Mark Warner again demonstrated the state’s slight pro-Democratic leaning, winning the close contest 50.4% to 49.6%.

The share-of-registration turnout was 20.3% for Warner and 20.0% for his Republican opponent.

There were also elections for the 11 US House of Representatives seats, which Republicans had won 8-3 two years earlier.

Democrats failed to nominate in two of the safe Republican-held seats, and Republicans likewise in the safest of the three seats with Democratic incumbents.

The aggregate vote totals thus appear to favour the Republican party.

But if the statewide Senate seat vote reveals a more accurate measure of the partisan divide, then Democrats might have expected to win 6 or 5 of the 11 seats. Instead, no seats changed hands at all: the Republicans held their 8 seats.

November 2015

The next year’s election was something of a democratic fiasco, with a voter turnout of just 25%. There was no president, state governor, or national Senate seat in play, so interest and campaigning effort were at their lowest ebb.

Just 9% of registered voters marked on their ballots votes up to support Democrat House of Delegates candidates. 15% of registered voters did so to support Republicans.

With incumbent Democrats defending only their 34 already-held seats, and overall the party only contesting a risible 56 of the 100 seat, the party’s poor turnout is hardly surprising.

By contrast the Republicans had 66 incumbents campaigning for re-election and a total of 73 nominees. So even in a very low-energy election, their relative outcome advantage is understandable.

And yet we know that part of the House aggregate vote is an artifact merely of voters having no candidate on the ballot paper to vote for, because 2015 was also the occasion for the 4-yearly election for the Virginia State Senate, which shows a somewhat different reality.

The state Senate has 40 seats, elected from a different map of 40 single-member divisions not matching the 100 districts where the House of Delegate members are elected.

The Senate district boundaries were also determined in the 2011-12 gerrymandering effort, but the larger geographical divisions will partly reduce the impact of gerrymandering.

Each party nominated candidates in 30 of the 40 Senate districts, leaving 10 of its opponent’s safest districts uncontested.

The registration-share result was 13.8% for the Republicans against 11.5% for the Democrats. This indicates that the low turnout in 2015, while still noticeably pro-Republican, was not as starkly so as the House aggregate vote numbers suggest.

The Republicans won 21 state Senate districts to the Democrats 19 – a majority that they will keep until the next elections are held in November 2019.

November 2016

In 2016, while Donald Trump was winning the support of the constitutional Electoral College to become the next President (while losing the national vote aggregate by nearly 3 million votes), Virginians again voted more favourably for Democratic party candidates.

Virginian voter turnout peaked at 71% for the election of a President. Hillary Clinton won this vote fairly clearly, by 50% to Trump’s 45%.

For the 11 Congressional House of Representatives seats, Democratic got their act together and contested all 11. Republicans skipped just one safe Democrat-held seat. Even noting that slight niggle in comparing their aggregate votes, the vote aggregate was 49.7% Democrat to 49.5% Republican (or if you prefer, 33.6% of registered voters for Democrats, and 33.3% for Republicans).

Such a result might finally have seen a 5-6 result in seat wins (one way or the other), but in fact Democrats picked up just one gain, based on substantial but localized surge of votes in the 4th district.

The Republicans therefore maintain a 7-4 advantage in the state’s seats in Congress, despite clearly not winning the support of a majority of the states voters in 2016.

November 2017

After the political tumults of Donald Trump’s election and the 2017 year in the Republican-controlled national congress, the Virginia Democratic party at last put proper effort into the 2017 elections, at which the state Governorship, the two other executive positions and the 100 House of Delegates seats were in play.

Democrats nominated in 88 of the 100 House seats – easily their best effort in modern times. Republicans nominated in 74 seats.

Turnout was a historically high 45% for the House elections.

A clear majority of votes favoured Democratic candidates, with 23.7% of registered voters voting for Democratic candidates, to 19.7% for Republicans. In vote share terms the result was 53% Democrat to 44% Republican.

Meanwhile, for the office of Governor 48% of registered voters actually turned out. (The slightly lower 45% for the House simply reflects those voters whose ballots did not present them with a meaningful contest in which to mark their ballot paper.)

Democratic candidate for Governor Ralph Northam (the incumbent Lieutenant Governor) won decisively, 54% to 45%. The races for the other two executive positions saw almost identical results.

The statewide partisan vote shares of 2017 are therefore consistently similar, and clearly favour Democrats.

So, did the Democrats at last achieve a majority in the state House of Delegates, breaking the power of the gerrymander?

No – they did not.

As we saw at the very beginning of this post, the Democrats picked off 15 of the Republican’s former 66-seat majority, but the gerrymander nonetheless preserved a 51-49 Republican seat advantage in the House.

The fiasco over resolving the result in the 94th district, with the 1-vote Democratic win, then the tie, then the drawing of the Republican name from the bowl – attracts attention for sheer farcical comedy, but in fact distracts attention from the fact that the Republicans have no business being anywhere near holding 50 or 51 seats.

Virginia’s voters – when they have turned out to vote in meaningful numbers – have been favouring Democratic executive and legislative options at state level – and at most of the federal level – for much of the past decade, and decisively expressed that intent in November 2017.

At peak elections Democratic support has been in a band from 33% to 36% of registered voters, with Republican support at 32% to 34%.

In the comparable off-peak elections (and leaving aside the dire 2015 turnout), Republican support has been at 19% to 21%, with Democratic support just very slightly higher at 20% to 21%. But at the 2017 vote the Democratic support broke from that range, rising to 24% to 25%.

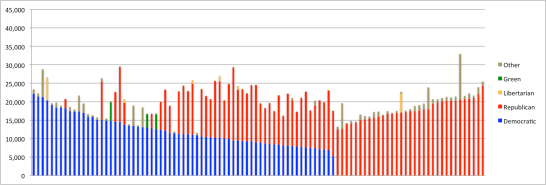

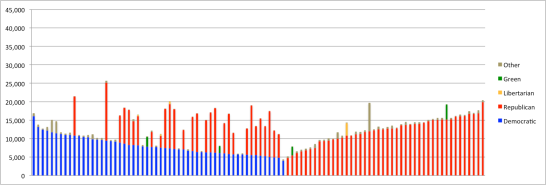

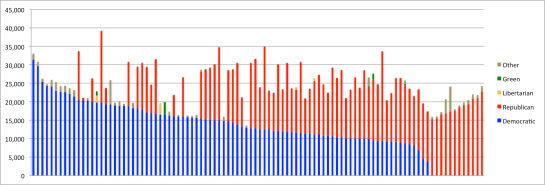

The three charts below show the Democrat challenge for, and votes won in, House of Delegates seats over the three elections in 2013, 2015 and 2017 (with the party’s best votes running from the left). The second chart shows the lacklustre nomination and vote-winning performance of 2015. But the third chart clearly shows that in 2017 the party not only nominated for many more seats, but won many more votes.

Democratic party nomination and vote performances for House of delegate seats, 2013-2017 (to same scale)

Yet Governor Northam will now need to contend politically with Republican majorities in both houses of the state legislature until the two houses jointly faces election in 2019.

That future election will once again be a low-interest midterm event that traditionally favours the Republican party.

The Virginian electorate has measurably preferred – and certainly now clearly prefers – Democratic governance, but is being denied it. The primary cause is clearly gerrymandering, including its effects over time in discouraging nominations and distorting election campaigns.

Low voter turnouts – which are endemic to US elections – are also to blame. Low turnouts render electoral systems more vulnerable to the impacts of gerrymandering, and in a vicious cycle, gerrymandering also acts to depress turnout.

The Virginian electoral authorities drew the name of Republican David Yancey from an ornate bowl yesterday, but there may be a few last legal moves to play out.

Democratic candidate Shelly Simonds is entitled to a recount, and the fact that the tie only occurred because the election panel reviewed just one ballot paper, chosen and presented to it by Republican lawyers – while other invalidated ballots that may have identical ambiguities were not brought forward for review – may yet come to be judicially examined.

And over in the 28th district, which the Republicans won by 73 votes, the awkward fact that just over twice as many voters were given ballots for the wrong district may also be challenged in court. (In Australia, a Court of Disputed Returns faced with such a defect in administering a close election would unhesitatingly void the election result and require a fresh poll.)

[Update: The federal court hearing this matter has declined to intercede, at least to prevent the elected Republican delegate from taking up the seat; the case will continue: Thomas to be seated, giving GOP control of Va. house, despite wrong votes (Wtop news).]

But in any case, the Republicans in the House of Delegates are now pressing on politically. By electing a House Speaker in the next few days – who can only later be removed by a two-thirds majority vote – they will shortly be able to appoint committee majorities and thereby dictate legislative procedures and control for the next few years, even if court challenges or special elections were to bring the House back into a 50-50 tie.

The state’s majority of Democratic supporters, it seems, have lost control of their own legislature, despite the electoral rituals by which they have attempting to elect its membership.

More reports:

Virginia clarifies the case against winner-take-all democracy, Lee Drutman, Vox

What Virginia tells us, and doesn’t tell us, about gerrymandering, Nicholas Stephanpopoulos, LA Times

A rare, random drawing helped Republicans win a tied Virginia election but it may not end there, Laura Vozzella, Washington Post

Earlier:

Virginia officials prepare for rare tie-breaking lottery that could determine political control of legislature, Laura Vozzella, Washington Post

(Note: The term ‘turnout’ used in this piece means proportion of registered voters voting. The more meaningful statistic would be proportion lf all eligible voters, using estimates such as those assembled by Michael McDonald, but that would have complicated what is already a data-heavy analysis.)

Pingback: US Gerrymandering declared unconstitutional – again | On Elections